Original equation image copyright fbatista72 / 123RF Stock Photo

In this article

Introduction

The Security Awareness market has existed in a recognisable form for about thirteen years now. Until very recently, however, solutions in the market have focussed almost exclusively on “training users" rather than actually changing people behaviour.

Perhaps it’s because of an underlying compliance driver for the deployment of Security Awareness solutions, but it often feels like the success criteria are “have I delivered training to users?” rather than “have I changed the security behaviour of users (and therefore reduced the risk to my business)?”.

BJ Fogg’s model

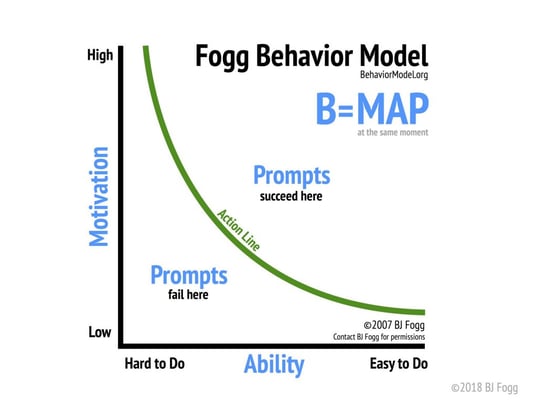

When considering behaviour change, BJ Fogg’s Behaviour Model is seminal. The model describes three components:

- Motivation – is my behaviour change target sufficiently motivated to change their behaviour?

- Ability – does my target have the capability to undertake the required behaviour modification?

- Prompt – is my target suitably prompted to affect the required behaviour change?

Fogg Behavior Model (behaviormodel.org) – reproduced with permission

The three components, M-A-P, are plotted on the above graph, with Ability and Motivation on the x- and y-axis respectively. The green line represents the point at which the desired behaviour change action occurs, with Prompting activities failing when the Motivation vs Ability point is positioned below the line and succeeding when it falls above it.

It’s worth bearing in mind that, as with Protection Motivation Theory, we should treat this as a model for how we might think about behaviour change; and accept that it’s an intentional abstraction of the many complexities of human cognition.

Science Applied: Strong and separate passwords

Let’s look at one aspect of Security Awareness through the lens of this model: strong and separate passwords.

It’s a typical requirement of organisational security policy that users should adopt passwords that are both strong (i.e. hard to guess) and separate (i.e. not used elsewhere). What does Fogg’s model tell us about how we might persuade people to do so?

Firstly, we can see that users need to be both Motivated and Able to perform our desired behaviour. The more motivated they are to undertake an activity, the harder they are prepared to work for it; and the easier an activity is to perform, the less motivated we need them to be. Another thing to realise is that we need just enough of both to push people across the line to where our Prompt will be effective.

Considering Ability

There’s a clear implication that the easier we make it to perform the target behaviour, the better. Asking users to set and remember (potentially numerous) long strings of random characters which change every few months is not easy. That’s why the NCSC now recommends not requiring frequent password changes, forming passwords from three random words, and saying that password managers are a “good thing”. All measures that push password policy compliance away from being “hard-to-do” and towards being “easy-to-do”.

Considering Motivation

The most important thing to recognise here is that Motivation is something that needs to be considered!

All-to-often in Security Awareness, Motivation is neglected, and users are expected to just “do their training”. Fogg describes the core human motivators as being pleasure/pain, hope/fear, and social acceptance/rejection. It appears that the default position with Security Awareness is to leverage fear (“if you don’t do X, attackers will steal all your data”) and pain (“if you don’t do Y, access will be revoked”) as core motivators. However, it’s worth considering social acceptance (“others are doing this, join the party”) as a more positive way of increasing Motivation.

Considering Prompts

Again, the primary thing to note is that appropriate Prompts need to be considered!

Behaviour change doesn’t just happen by magic because you want it to. In fact, it’s underpinned by providing the user with the right cue at the right time (the “opportune moment”) to undertake the target behaviour. Bear in mind that Prompts don’t work if Motivation and Ability are not squared away. Our observation, though, is that Prompts are almost entirely absent from Security Awareness.

Science Applied: A password prompt

When it comes to passwords, behaviour change won’t simply happen by making people aware of password policy on an annual basis via mandatory training: annual training is just about the worst Prompt for action we can imagine. So, when is the opportune moment to trigger behaviour change around password policy? What about when people are changing their password!

Are you wondering how a Prompt can be delivered at that particular point in time? Book a 15 min Demo!

In summary, true behaviour change isn’t as easy as it looks. But consider B=MAP when designing a Security Awareness programme might be a good first step.